Always Looking – People Who Made A Difference XXVI

Always Looking – People Who Made A Difference XXVI

By

John I. Blair

Nathaniel Bowditch

Nathaniel Bowditch (1773-1838), a self-taught astronomer, navigator, and business executive, was one of America's first scientists. His reputation is based on two books; the New American Practical Navigator – a manual for sailors that is still in print – and his translation of French mathematician Pierre Laplace's Méchanique Céleste (celestial mechanics).

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, Nathaniel was the fourth child of a cooper (barrel maker) and shipmaster. At age 10 he went to work beside his father at a cooperage. In 1785, age 12, Nathaniel was apprenticed to ship chandlers (providers of necessary supplies to sailing ships). Living in the house of Jonathan Hodges, he was allowed to use his master's library. During the day he learned about the equipment and supplies needed to outfit sailing ships and heard stories of exotic ports and people. In the evenings he studied in the library.

Salem's sea-going merchants generated wealth that supported scientific development and instrument making. In these fields Bowditch was encouraged by three local Harvard-trained scholars: Nathan Read, an apothecary, nail factory owner, and early steam engine and paddlewheel boat inventor; John Prince, the liberal pastor of the First Congregational Church of Salem and the inventor of an air pump; and William Bentley, pastor of the Second Congregational Church. Bentley encouraged Bowditch to study Latin and, from his 4,000 book library, lent him books, including Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica. In 1791 the Philosophical Library Society, at the urging of Bentley and Prince, granted 18-year old Bowditch borrowing privileges. With these resources he continued his readings in mathematics and natural philosophy, mastered Euclid’s writings on mathematics and geometry, and learned French by translating the New Testament with the help of a dictionary. He also constructed his own astronomical and surveying instruments.

In 1794 Bowditch assisted Reverend Bentley and shipmaster John Gibaut in a land survey of Salem. Gibaut was so impressed with the young man's thoroughness and accuracy that he invited Bowditch to sign on as clerk on his next voyage to the East Indies. In preparation, Bowditch took up the study of sea journals and navigation techniques. Between 1795 and 1803, Bowditch sailed to the East Indies five times. He used his free time on board studying sailing charts and navigation, taking lunar measurements, and filling notebooks with observations. The first time he signed on as a clerk and second mate; by the last voyage he was master and part-owner of the ship. After selling his goods from the last voyage, he had enough capital to retire from the sea.

Practical sailing experience combined with astronomy scholarship made Bowditch one of the best navigators in America. Newburyport publisher Edmund March Blunt commissioned him to update and revise his The American Coast Pilot, 1796. Bowditch used a 15-month stretch of shore time, 1797-98, to check the data and recalculate the tables. Building on his work on The American Coast Pilot, in 1802 Bowditch compiled The New American Practical Navigator. As secretary and inspector of voyage journals for the East India Marine Society of Salem, he had access to additional information on voyages, routes, and foreign ports. The New American Practical Navigator contained instruction in navigation, surveying directions, data on winds, directions on how to calculate high tides, notes on currents, a dictionary of sea terms, an explanation of rigging, model contracts, a model ship's journal or log, statistics on marine insurance, information on bills of exchange, and lists of responsibilities for ship owners, masters, factors, and agents. This comprehensiveness soon won it wide usage and the title of "the seaman's bible." It went through ten editions before Bowditch died.

|

Clipper Ships similar to those in Bowditch's lifetime. |

In 1799 Bowditch was elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and was its president from 1829-1838. In 1818 he was elected to the Edinburgh and London Royal Societies. He later joined the Irish Royal Academy, the Royal Astronomical Society of London, the Royal Academies of Palermo and Berlin, and the British Association.

Beginning in 1812 Bowditch worked on an English translation of Pierre Laplace's Traité de mécanique céleste and he wrote scientific articles on spherical trigonometry, magnetic compass variations, the earth's oblateness, celestial table corrections, and the behavior of twin pendulums. These articles appeared in the Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. In addition, he wrote a number of extended book reviews for the North American Review. He self-published his four-volume translation of Laplace, 1829-39, using one-third of his life savings. Complimentary copies were sent to libraries and scientists around the world. The books contained three pages of annotations for every two in the original. His protégé and editorial assistant on the project, Benjamin Pierce, went on to become a Harvard professor and America's leading mathematician. The translation trained the next generation of American astronomers.

|

Bowditch House in Salem |

In 1823, at the age of 50, Bowditch moved to Boston to become the actuary of the Massachusetts Hospital Life Insurance Company. He joined the Church on the Green led by the Unitarian minister, Alexander Young, and attended the Sunday evening salons at the home of his friend, Harvard professor George Ticknor. There he mixed with many of Boston's intellectuals, including William Prescott and Daniel Webster.

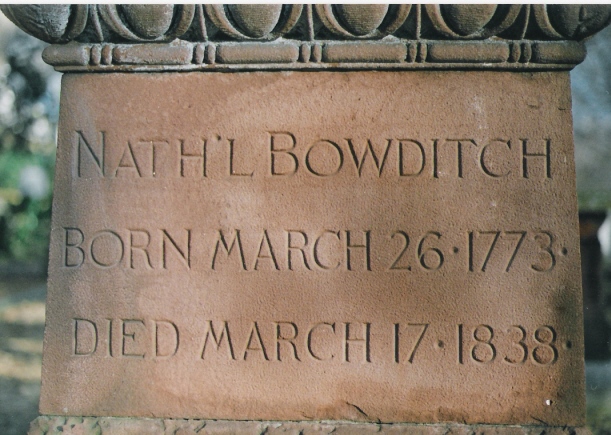

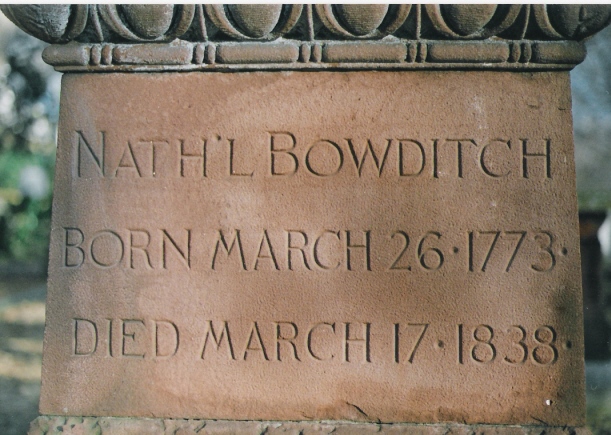

After his wife’s death in 1834, Nathaniel slowed down, taking more time to read poetry, history and biography. He died at 65 and was buried beside his wife under Trinity Church in Boston. Later they were reburied in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

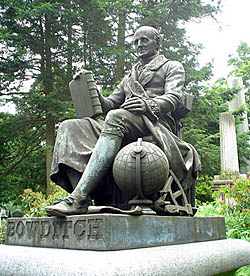

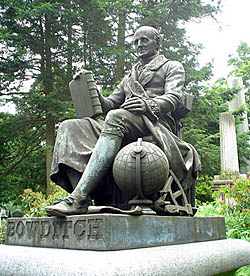

Bowditch close up and Statue |

|

Bowditch attended church all his life. He was reticent about his religious beliefs, particularly those that might not be universally shared. Rev. Young said, "In his religious views, Dr. Bowditch was, from examination and conviction, a firm and decided Unitarian. But he had no taste for the polemics or peculiarities of any sect, and did not love to dwell on the distinctive and dividing points of Christian doctrine. His religion was rather an inward sentiment, flowing out into the life, and revealing itself in his character and actions."

When asked about his religious beliefs Bowditch answered, "Of what importance are my opinions to anyone? I do not wish to be made a show of. As to creeds of faith, I have always been of the sentiment of the poet (Alexander Pope, “Essay on Man”),—'For modes of faith let graceless zealots fight; His can't be wrong, whose life is in the right.'"

Bowditch's grave marker shown at bottom of page.

Adapted from the article in Dictionary of Unitarian Universalist Biography at uudb.org/articles/nathanielbowditch

Researched and compiled by John I. Blair

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

|